Battle of France

The Battle of France is a major theatre in WW2, that encompassed many smaller campaigns, such as the Battle of Arras, Battle of The Netherlands, and Battle of Belgium.

Battle of Arras

21 May 1940

Theatre: France

Area: The town of Arras in Northern France, on the River Scarpe south west of Lille.

Players: Britain: 6th and 8th Battalions, Durham Light Infantry; 4th and 7th Battalions, Royal Tank Regiment. Germany: 7th Panzer Division; German 7th Infantry Regiment and SS Totenkopf Division.

Outcome: This British counter-attack failed, but nonetheless worried the advancing Germans and possibly contributed to the success of the Dunkirk evacuation.

The Battle of Arras, in 1940, was the first effective Allied counterattack against German forces in World War II and a battle which tanks were heavily involved. It was part of the Battle of France, in which the Nazis invaded France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

On May 10, 1940, Germany commenced its invasion of France.

The German panzer divisions were able to cross the Meuse River quickly and easily, catching many of the French forces by surprise.

Although the panzers could not do much damage to the heavy French Char 1s, the Germans were able to beat the French simply by being more organized and having a more up-to-date battle plan.

As the Germans advanced rapidly towards the French coast in May 1940, the area around the town of Arras was reinforced with British Expeditionary Force (BEF) troops.

The French were still using World War I tactics. The French strategy was for forces to remain in static positions along the borders and for infantry, supported by tanks, to be used to drive back enemy assaults.

Char B1. At the start of WW2, this tank was one of the heaviest in the world

By this time, however, the Germans had learned that using up a great deal of resources in order to defeat one enemy stronghold was unproductive. Therefore, they moved their tanks quickly, passing areas where the French were strong and attacking from unexpected directions.

The Nazis also learned how to exploit the Char 1's flaws. For example, they discovered that they could immobilize the French tanks by shooting their tracks and radiator louvers.

The Char 1's hull-mounted gun could only fire forwards, so German tanks could avoid the gun by approaching the Char from the side. The turret gun could still be used against the panzers. However, the turret gun was operated by the tank commander, who also had to perform other tasks. This reduced his effectiveness as a gunner.

The British Expeditionary force(BEF)

The Germans were able to advance through France at a speed of 50 miles (80 kilometers) a day.

By 20 May 1940, Arras itself was surrounded but still holding out. General Erwin Rommel, commander of the German 7th Armoured division decided to attack the British at Arras.

Two British infantry divisions could not stop the German advance. The Germans were able to surround Arras, separating the British from their lines of communication.

The German high command then ordered their forces to halt.

On May 22, 1940, the Germans received orders to advance on Arras once more.

However, more British tanks had arrived at Arras on May 21. There were now two British tank regiments, supported by two Territorial Infantry battalions, trying to prevent the Germans from overrunning British headquarters.

Viscount Gort, commander-in-chief of the BEF, decided on a counter-attack codenamed Frankforce.

The British launched a counterattack against the Germans, using 76 Mark I and Mark II infantry tanks (Matildas). There 58 Mark Is and 16 Mark IIs.

Although the Mark IIs had 2 pounder guns, the Mark Is, which made up the majority of the British tanks, had only machine guns as weapons.

The attack was supposed to be manned by two infantry divisions, comprising about 15,000 men. It was ultimately executed by just two infantry battalions totaling around 2,000 men and reinforced by 74 tanks.

The infantry battalions were split into two columns for the attack, which took place on 21 May.

Because the British infantry was worn out by this time, British tanks at first moved forward without infantry support. The infantry caught up with the tanks later.

The British caught the Nazis by surprise, just one hour before the German attack on Arras had been scheduled to begin. British tanks were used to attack the 7th Armored Division and the SS Totenkopf (Death's Head) Division. The Totenkopf division retreated in panic.

Matilda Mk 1.

Matilda Mk2

German antitank gunners tried firing at the Matildas, but their rounds bounced of the British tanks.

The Matildas - even those that had only machine guns - were very effective against German anti-tank gunners.

Interestingly, a flaw in the Matildas' design helped the British forces.

The Matildas' external stowage bins, which held the tank crew's extra gear, had a tendency to catch fire when they were shot at. This did not affect the crew's ability to drive the tank.

From a distance, it looked like the whole tank was on fire. German soldiers were terrified when they saw British tanks being driven while they were apparently engulfed in flames - making the British tanks, and the British tank crews, seem indestructible.

British Matilda Mk2s, still engaging in combat despite catching fire

Erwin Rommel, arguably the most famous of the German Generals in WW2.

Rommel tried to help the German situation by personally directing field artillery crews and anti-aircraft gun crews. He ran among the crews, ordering them to fire at British tanks.

The right column initially made rapid progress, taking a number of German prisoners, but they soon ran into German infantry and SS, backed by air support, and took heavy losses.

The left column also enjoyed early success before running into opposition from the infantry units of Brigadier Erwin Rommel's 7th Panzer Division.

French cover enabled British troops to withdraw to their former positions that night. Frankforce was over, and the next day the Germans regrouped and continued their advance.

Frankforce took around 400 German prisoners and inflicted a similar number of casualties, as well as destroying a number of tanks. The operation had punched far beyond its weight - the attack was so fierce that 7th Panzer Division believed it had been attacked by five infantry divisions. Worried of losing more valuable tanks, German forces halted their plans to attack.

The panic ‘Frankforce’ created may have been one of the factors for the surprise German halt on 24 May that gave the BEF the slimmest of opportunities to begin evacuation from Dunkirk.

Battle of The Netherlands and Begium

May: Fall Gelb, Low Countries, and northern France

The North

Germany initiated Fall Gelb on the evening prior to and the night of 10 May. During the late evening of May 9, German forces occupied Luxembourg. In the night Army Group B launched its feint offensive into the Netherlands and Belgium.

Fallschirmjägers (paratroopers) from the 7th and 22nd Fliegel divisions and Luftlande Infanterie-Division under Kurt Student executed surprise landings that morning at The Hague, on the road to Rotterdam and against the Belgian Fort Eben-Emael in order to facilitate Army Group B's advance.

The French command reacted immediately, sending its First Army Group north in accordance with Plan D. This move committed their best forces, diminished their fighting power through loss of readiness and their mobility through loss of fuel. That evening the French Seventh Army crossed the Dutch border, only to find the Dutch already in full retreat. The French and British air command was less effective than their generals had anticipated, and the Luftwaffe quickly obtained air superiority, depriving the Allies of key reconnaissance abilities and disrupting Allied communication and coordination.

The Netherlands

The Luftwaffe was guaranteed air superiority over the Netherlands. The Dutch Air Force, the Militaire Luchtvaartafdeling (ML), had 144 combat aircraft, half of which were destroyed within the first day of operations. The remainder was dispersed and accounted for only a handful of Luftwaffe aircraft shot down. In total, the ML flew a mere 332 sorties losing 110 of its aircraft.

The German 18th Army secured all the strategically vital bridges in and toward Rotterdam, which penetrated Fortress Holland and bypassed the New Water Line from the south. However, an operation organized separately by the Luftwaffe to seize the Dutch seat of government, known as the Battle for The Hague, ended in complete failure. The airfields surrounding the city (Ypenburg, Ockenburg, and Valkenburg) were taken with heavy casualties and transport aircraft losses, only to be lost that same day to counterattacks by the two Dutch reserve infantry divisions. The Dutch captured or killed 1,745 Fallschirmjäger, shipping 1200 prisoners to England.

The Luftwaffe's Transportgruppen also suffered heavily. Transporting the German paratroopers had cost it 125 Junkers; of which 52 destroyed and 47 damaged, representing 50 percent of the fleet's strength. Most of these transports were destroyed on the ground, and some while trying to land under fire, as German forces had not properly secured the airfields and landing zones.

A burned out German Junkers Ju 52 transport lying in a Dutch field. 50 percent of the Luftwaffe's Transportgruppenwas destroyed during the assault

German He 111 bomber

The French Seventh Army failed to block the German armored reinforcements from the 9th Panzer Division, which they reached Rotterdam on 13 May. That same day in the east, following the Battle of the Grebbeberg in which a Dutch counter-offensive to contain a German breach had failed, the Dutch retreated from the Grebbe line to the New Water Line.

The Dutch Army, still largely intact, surrendered in the evening of May 14 after the Bombing of Rotterdam by Heinkel He 111s of Kampfgeschwader 54 (specialized bomber units). It considered its strategic situation to have become hopeless and feared further destruction of the major Dutch cities. The capitulation document was signed on 15 May. However, the Dutch troops in Zeeland and the colonies continued the fight while Queen Wilhelmina established a government-in-exile in Britain.

Fort Eben Emael

KW positions

Hotchkiss H35 tanks

Somua S35 tanks

Central Belgium

The Germans were able to establish air superiority in Belgium with ease. Having completed thorough photographic reconnaissance missions, they destroyed 83 of the 179 aircraft of the Aeronautique Militaire within the first 24 hours. The Belgians would fly on 77 operational missions but would contribute little to the air campaign. The Luftwaffe has assured air superiority over the Low Countries.

Because German Army Group B had been so weakened compared to the earlier plans, the feint offensive by German Sixth Army was in danger of stalling immediately since the Belgian defences on the Albert Canal position were very strong. The main approach route was blocked by Fort Eben-Emael, a large fortress then generally considered the most modern in the world, controlling the junction of the Meuse and the Albert Canal. Any delay might endanger the outcome of the entire campaign, because it was essential that the main body of Allied troops was engaged before Army Group A would establish bridgeheads.

To overcome this difficulty, the Germans resorted to unconventional means in the Battle of Fort Eben-Emael. In the early hours of May 10 gliders landed on the roof of Fort Eben-Emael unloading assault teams that disabled the main gun cupolas with hollow charges. The bridges over the canal were seized by German paratroopers. Shocked by a breach in its defenses just where they had seemed the strongest, the Belgian Supreme Command withdrew its divisions to the KW-line five days earlier than planned. At that moment however the BEF and the French First Army were not yet entrenched. When Erich Hoepner's XVI Panzer Corps, consisting of 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions was launched over the over the newly-captured bridges in the direction of the Gembloux Gap, this seemed to confirm the expectations of the French Supreme Command that the

German Schwerpunkt would be at that point. The two French Light Mechanized divisions, the 2nd DLM and 3rd DLM were ordered forward to meet the German armour and cover the entrenchment of the First Army. The resulting Battle of Hannut, which took place on May 12 and May 13, was the largest tank battle until that date, with about 1500 AFVs participating. The French claimed to have disabled about 160 German tanks for 91 Hotchkiss H35 and 30 Somua S35 tanks destroyed or captured. However, as the Germans controlled the battlefield area afterwards, they recovered and eventually repaired or rebuilt many of the Panzers: German irreparable losses amounted to 49 tanks (20 Panzer IIIs and 29 Panzer IVs).

The German armour sustained substantial breakdown rates making it impossible to ascertain the exact number of tanks disabled by French action. On the second day the Germans managed to breach the screen of French tanks, which were successfully withdrawn on May 14 after having gained enough time for the First Army to dig in. Hoepner tried to break the French line on May 15 against orders, the only time in the campaign when German armour frontally attacked a strongly held fortified position. The attempt was repelled by the 1st Moroccan Infantry Division, costing 4th Panzer Division another 42 tanks, 26 of which were irreparable. This defensive success for the French was however already made irrelevant by the events further south.

King Leopold III would later surrender on the 27th of May which would later complicate the positions for the Allies during the evacuation of Dunkirk.

Panzer III(left) and Panzer IV(above)

The Centre

In the center, the progress of German Army Group A was to be delayed by Belgian motorized infantry and French Mechanized Cavalry divisions (Divisions Légères de Cavalerie) advancing into the Ardennes. These forces however had an insufficient anti-tank capacity to block the surprisingly large number of German tanks they encountered and quickly gave way, withdrawing behind the Meuse. The German advance was however greatly hampered by the sheer number of troops trying to force their way through the poor road network. Kleist's Panzer Group had more than 41,000 vehicles. To traverse the Ardennes Mountains, this huge armada of vehicles had been granted only four march routes. The time-tables proved to have been wildly optimistic and soon traffic congestion formed, beginning well over the Rhine to the east that would last for almost two weeks. This made Army Group ‘A’ very vulnerable to French air attacks, but these did not materialize.

Although Gamelin was well aware of the situation, the French tactical bomber force was far too weak to challenge German air superiority so close to the German border. However, on 11 May Gamelin ordered many reserve divisions to begin reinforcing the Meuse sector. Because of the danger, the Luftwaffe posed, movement over the rail network was limited to the night, slowing the reinforcement, but the French felt no sense of urgency as the build-up of German divisions would be accordingly slow.

The German advance forces reached the Meuse line late in the afternoon of May 12. To allow each of the three armies of Army Group A to cross, three major bridgeheads were to be established: at Sedan in the south, at Monthermé 20 kilometers to the northwest and at Dinant, another fifty kilometers to the north. The first units to arrive had hardly even a local numerical superiority; their already insufficient artillery support was further limited by an average supply of just 12 rounds apiece.

By this time, the Belgian line had already fallen much earlier than expected and the capture of Paris would come with weeks.

Battle of France

On May 13, the German XIX Army Corps forced three crossings near Sedan, executed by the motorized infantry regiments of 1st, 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions, reinforced by the elite Großdeutschland(German for "Greater Germany" )infantry regiment (It was the best equipped division in the German army).

Instead of slowly massing artillery as the French expected, the Germans concentrated most of their tactical bomber force to punch a hole in a narrow sector of the French lines by carpet bombing punctuated by dive bombing. Hermann Göring had promised Guderian that there would be an extraordinary heavy air support of a continual eight hour air attack, from 8am until dusk. Luftflotte 3, supported by Luftflotte 2, executed the heaviest air bombardment the world had yet witnessed and the most intense by the Luftwaffe during the war. The Luftwaffe committed two Stukageschwader (Luftwaffe dive-bomber air wing) to the assault flying 300 sorties against French positions, with Stukageschwader 77 alone flying 201 individual missions. By the nine Kampfgeschwader (medium bomber units - See Luftwaffe Organization) committed, a total of 3,940 sorties were flown, often in Gruppe strength.

An illustrated depiction of the elite panzer division which would be critical to the success of the Blitzkrieg

Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers used by the Germans

The forward platoons and pillboxes of the 147 RIF were little affected by the bombardment and held their positions throughout most of the day, initially repulsing the crossing attempts of 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions on their left and right. However, there was a gap in the line of bunkers in the center of the river bend. In the late afternoon, Großdeutschland penetrated this position, trying to quickly exploit this opportunity. The deep French zone defense had been devised to defeat just this kind of infiltration tactics; it now transpired however that the morale of the deeper company positions of the 55e DI had been broken by the impact of the German air attacks. They had been routed or were too dazed to offer effective resistance any longer. The French supporting artillery batteries had fled, and this created an impression among the remaining main defense line troops of the 55e DI that they were isolated and abandoned. They too went into a rout by the late evening. At a cost of a few hundred casualties, the German infantry had penetrated up to 8 kilometers (5.0 mi) into the French defense zone by midnight. Even then, most of the infantry had not crossed yet, much of the success is from the actions of just six platoons, mainly assault engineers.

The disorder that had begun at Sedan was spread down the French lines by groups of haggard and retreating soldiers. At 19:00 hrs on May 13, the 295th regiment of 55e DI, holding the last prepared defense line at the Bulson ridge, 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) from the Meuse, was panicked by the false rumor that German tanks were already behind its positions. It fled, creating a gap in the French defenses before even a single German tank had crossed the river. This "Panic of Bulson" or phénomène hallucination involved the divisional artillery so that the crossing sites were no longer within range of the French batteries. The division dissolved and ceased to exist. The Germans had not attacked their position, and would not do so until 12 hours later.

In the morning of May 14, two French FCM 36 tank battalions (4 and 7 BCC) and the reserve regiment of 55e DI, 213rd RI, executed a counterattack on the German bridgehead. It was repulsed at Bulson by the first German armour and anti-tank units which had been rushed across the river from 07:20 on the first pontoon bridge.

Infamous German 88mm Flak cannon. It was capable of taking out any bombers or tanks the Allies had in its arsenal

General Gaston-Henri Billotte, commander of the First Army Group whose right flank pivoted on Sedan, urged the bridges across the Meuse River to be destroyed by air attack, convinced that "over them will pass either victory or defeat!" That day every available Allied light bomber was employed in an attempt to destroy the three bridges, but failed to hit them while suffering heavy losses. The RAF Advanced Air Striking Force under the command of Air Vice-Marshal P H L Playfair bore the brunt of the attacks. The plan called for the RAF to commit its bombers for the attack while they would receive protection from the French fighter groups.

The British bombers received insufficient air cover and as a result some 21 French fighters and 48 British bombers, 44 percent of the A.A.S.F's strength, was destroyed by Oberst Gerd von Massow's Jagdfliegerführer 3 Jagdgruppen. The French Armée de l'Air also tried to halt the German armored columns, but the small French bomber force had been so badly mauled the previous days, that only a couple dozen aircraft could be committed over that vital target. Two French bombers were shot down. The German anti-aircraft defenses, consisting of 198 88 mm, 54 43.7 cm and 81 20 mm cannon accounted for half of the Allied bombers destroyed. In just one day the Allies lost ninety bombers. In the Luftwaffe, it became known as the "Day of the Fighters".

The commander of XIX Army Corps, Heinz Guderian, had indicated on May 12 that he wanted to enlarge the bridgehead to at least 20 kilometers (12 mi). His superior, Ewald von Kleist, however ordered him to limit it to a maximum of 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) before consolidation. On May 14 at 11:45, von Rundstedt confirmed this order, which basically implied that the tanks should now start to dig in. Nevertheless Guderian immediately disobeyed, expanding the perimeter to the west and to the south.

In the original von Manstein Plan as Guderian had suggested it; secondary attacks would be carried out to the southeast, in the rear of the Maginot Line, to confuse the French command. This element had been removed by Halder but Guderian now sent 10th Panzer Division and Großdeutschland south to execute precisely such a feint attack, using the only available route south over the Stonne plateau. However, the commander of the French Second Army, General Charles Huntzinger, intended to carry out a counterattack at the same spot by the armoured 3e Division Cuirassée de Réserve (DCR) to eliminate the bridgehead. This resulted in an armoured collision, both parties in vain trying to gain ground in furious attacks from May 15 to May 18, the village of Stonne changing hands many times. Huntzinger considered this at least a defensive success and limited his efforts to protecting his flank. However, in the evening of May 16, Guderian removed 10th Panzer Division from the effort, having found a better destination for it.

Guderian had turned his other two armoured divisions, the 1st Panzer Division and 2nd Panzer Division sharply to the west on May 14. In the afternoon of 14 May there was still a chance for the French to attack the exposed southern flank of 1st Panzer Division before 10th Panzer Division had entered the bridgehead, but it was thrown away when the planned attack by 3 DCR was delayed because it was not ready in time.

On May 15, in heavy fighting, Guderian's motorized infantry dispersed the reinforcements of the newly formed French Sixth Army in their assembly area west of Sedan, undercutting the southern flank of the French Ninth Army by 40 kilometres (25 mi) and forcing the 102nd Fortress Division to leave its positions that had blocked the tanks of XVI Army Corps at Monthermé. The French Second Army had been seriously mauled and had rendered itself impotent. While this was happening, the French Ninth Army began to disintegrate completely. This Army had already been reduced in size because some of its divisions were still in Belgium. They also did not have time to fortify and had been pushed back from the river by the unrelenting pressure of the attacking German infantry. This allowed the impetuous Erwin Rommel to break free with his 7th Panzer Division. Rommel had advanced quickly and his lines of communications with his superior, General Hermann Hoth and his Headquarters were cut. Using the Mission Command system to full effect, and not waiting for the French to establish a new line of defence, he continued to advance. The French 5th Motorized Infantry Division was sent to block him, but the Germans were advancing unexpectedly fast, and Rommel surprised the French vehicles while they were refuelling on 15 May. The Germans were able to fire directly into the neatly lined French vehicles and overran their position completely. The French unit had "disintegrated into a wave of refugees; they had been overrun literally in their sleep". By May 17, Rommel had taken 10,000 prisoners and suffered only 36 losses.

Von Rundstedt(left)and Heinz Guderian(right)

Blitzkrieg

According to the original plan of Halder, the Panzer Corps now had fulfilled a precisely circumscribed task. Their motorized infantry component had secured the river crossings and their tank regiments had conquered a dominant position. Now they had to consolidate, allowing the three dozen infantry divisions following them to position themselves for the real battle: perhaps a classic Kesselschlacht (Kesselschlacht (literally, "cauldron battle")) if the enemy should stay in the north or perhaps an encounter fight if he should try to escape to the south. In both cases an enormous mass of German divisions, both armoured and infantry, would act in close cooperation to annihilate the enemy. The Panzer Corps was not to bring about the collapse of the enemy by themselves. The plan called for the Germans to build up forces for a period of about five days.

On 16 May however, both Guderian and Rommel disobeyed their explicit direct orders in an act of open insubordination against their superiors. They broke out of their bridgeheads and moved their divisions many kilometres to the west as fast as they could push them. Guderian reached Marle, eighty kilometers from Sedan, while Rommel crossed the river Sambre at Le Cateau, a hundred kilometers from his bridgehead at Dinant.

The interpretation of the actions of both generals has remained deeply controversial and is connected to the problem of the precise nature and origin of Blitzkrieg tactics, of which the 1940 campaign is often described as a classic example. An essential element of Blitzkrieg was considered to be a strategic envelopment executed by mechanized forces which led to the operational collapse of the defender. It has also been looked at as a novel, revolutionary, form of warfare. After the war, Guderian claimed to have acted on his own initiative, essentially inventing this classic form of Blitzkrieg on the spot. The traditional interpretation accepts the novel character of the Blitzkrieg tactic but considers Guderian's claim to be an empty boast, denying any fundamental divide within contemporaneous German operational doctrine, downplaying the internal German conflict as a mere difference of opinion about timing and pointing out that Guderian's claim is inconsistent with his professed rôle as the prophet of Blitzkrieg even before the war. It is seen as an anomaly that there is no explicit reference to such tactics in the German battle plans. A second, later, main interpretation also sees Blitzkrieg as revolutionary, but denies that it was in accordance with established doctrine, vindicating Guderian. In this view the Battle of France is the first historical instance of Blitzkrieg

While nobody knew the whereabouts of Rommel (he had advanced so quickly that he was out of range for radio contact, earning his 7th Panzer Division]] the nickname Gespenster-Division, "Ghost Division"), an enraged von Kleist flew to Guderian's position on the morning of 17 May and after a heated argument, relieved him of all duties. However, von Rundstedt refused to confirm the order.

Allied reaction

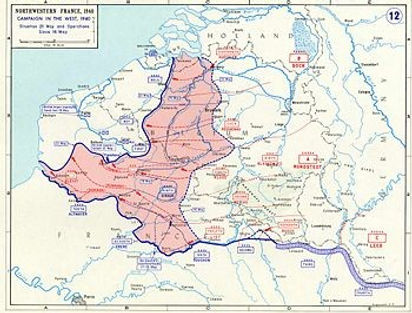

The German advance up to 21 May 1940

The Panzer Corps now slowed their advance considerably and had put themselves in a very vulnerable position. They were stretched out, exhausted, low on fuel, and many tanks had broken down. There was now a dangerous gap between them and the infantry. A determined attack by a fresh and large enough mechanized force could have cut the Panzers off and wiped them out.

The French High Command, however, was reeling from the shock of the sudden offensive and was now stung by a sense of defeatism. On the morning of 15 May French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud telephoned the new Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Winston Churchill and said "We have been defeated. We are beaten; we have lost the battle." Churchill, attempting to console Reynaud, reminded the Prime Minister of the all the times the Germans had broken through the Allied lines in World War I only to be stopped. However, Reynaud was inconsolable.

Churchill flew to Paris on 16 May. He immediately recognized the gravity of the situation when he observed that the French government was already burning its archives and was preparing for an evacuation of the capital. In a somber meeting with the French commanders, Churchill asked General Gamelin, "Où est la masse de maneuver?" ["Where is the strategic reserve?"] that had saved Paris in the First World War. "Aucune" ["There is none,"] Gamelin replied. Later, Churchill described hearing this as the single most shocking moment in his life. Churchill asked Gamelin where and when the general proposed to launch a counterattack against the flanks of the German bulge. Gamelin simply replied "inferiority of numbers, the inferiority of equipment, and inferiority of methods".

Gamelin was right. Most of the French reserve divisions had by now been committed. The only armored division still in reserve, 2nd DCR, attacked on May 16. However, the French reserve armored divisions, the Divisions Cuirassées de Réserve, were despite their name, very specialized breakthrough units, optimized for attacking fortified positions. They could be quite useful for defense, if dug in, but had very limited utility for an encounter fight. They could not execute combined infantry-tank tactics because they simply had no important motorized infantry component. They also suffered from poor tactical mobility because their heavy Char B1 bis tanks, in which half of the French tank budget had been invested had to refuel twice a day. So the 2nd DCR was forced to divide them into a covering screen. The 2nd DCR's small subunits fought bravely but with little strategic effect.

Some of the best units in the north, however, had seen little fighting. Had they been kept in reserve they could have been used for a decisive counter strike. However, they had lost much of their fighting power by simply moving to the north and if they were forced to hurry south again it would cost them even more. The most powerful Allied division, the French 1st Light Mechanized Division, had been deployed near Dunkirk on May 10. It had moved its forward units 220 kilometers (140 mi) to the northeast, beyond the Dutch city of Hertogenbosch in just 32 hours. Upon finding that the Dutch army had already retreated to the north, they withdrew, and moved back to the south. When it reached the German lines again, only three of its 80 SOMUA S 35 tanks were operational, mostly as a result of breakdown.

Nevertheless, a radical decision to retreat to the south, while avoiding contact, could probably have saved most of the mechanized and motorized divisions, including the BEF. However, that would have meant leaving about thirty infantry divisions to their fate. The loss of Belgium alone would be seen as an enormous political blow. Besides, the Allies were uncertain about what the Germans would do next. They threatened in four directions: to the north, to attack the Allied main force directly; to the west, to cut it off; to the south, to occupy Paris and even to the east, to move behind the Maginot Line. The French response was to create a new reserve under General Touchon, among which was a reconstituted Seventh Army, using every unit they could safely pull out of the Maginot Line to block the way to Paris.

Colonel Charles de Gaulle, in command of France's hastily formed 4th DCR, attempted to launch an attack from the south which achieved a measure of success. This attack would later accord him considerable fame and a promotion to Brigadier General. However, de Gaulle's attacks on May 17 and 19 did not significantly alter the overall situation.

German advance to the Channel

The Allies did little either to threaten the Panzer Corps or escape from the danger they posed. So the Panzer troops used May 17 and 18 May to refuel, eat, sleep, and put more tanks in working order. On May 18 Rommel caused the French to give up Cambrai by merely executing a feint armoured attack towards the city.

The Allies seemed incapable of coping with events. On May 19, General Ironside, the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff, conferred with General Gort, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, at his headquarters near Lens. Gort reported that the Commander of the French Northern Army Group, General Billotte, had given him no orders for eight days. Ironside confronted Billotte, whose own headquarters was nearby, and found him apparently incapable of taking decisive action.

Ironside had originally urged Gort to save the BEF by attacking south-west towards Amiens. Gort replied that seven of his nine divisions were already engaged on the Scheldt River, and he had only two divisions left with which he would be able to mount such an attack. Ironside returned to Britain concerned that the BEF was already doomed, and ordered urgent anti-invasion measures.

On that same day, the German High Command grew very confident. They determined that there appeared to be no serious threat to them from the south. In fact, General Franz Halder toyed with the idea of attacking Paris immediately to knock France out of the war with one blow. The Allied troops in the north were retreating to the river Scheldt which exposed their right flank to the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions. It would have been foolish for the Germans to remain inactive any longer since it would allow the Allies to reorganize their defence or escape. It was now time for the Germans to attempt to cut off the Allies' escape. The next day the Panzer Corps started moving again and smashed through the weak British 18th and 23rd Territorial Divisions. The Panzer Corps occupied Amiens and secured the westernmost bridge over the river Somme at Abbeville. This move isolated the British, French, Dutch, and Belgian forces in the north. That evening, a reconnaissance unit from 2nd Panzer Division reached Noyelles-sur-Mer, 100 kilometers (62 mi) to the west. From there they were able to see the estuary of the Somme flowing into the English Channel.

Fliegerkorps VIII under the command of Wolfram von Richthofen committed its StG 77 and StG 2 to covering this "dash to the channel coast." Heralded as the Stukas' "finest hour" these units responded via an extremely efficient communications system to the Panzer Divisions' every request for support, which effectively blasted a path for the Army. The Ju 87s were particularly effective at breaking up attacks along the flanks of the German forces, breaking fortified positions, and disrupting rear-area supply chains. The Luftwaffe also benefitted from excellent ground-to-air communications throughout the campaign. Radio equipped forward liaison officers could call upon the Stukas and direct them to attack enemy positions along the axis of advance. In some cases the Stukas responded to requests in 10-20 minutes. Oberstleutnant Hans Seidmann (Richthofen's Chief of Staff) said that "never again was such a smoothly functioning system for discussing and planning joint operations achieved."

Weygand Plan

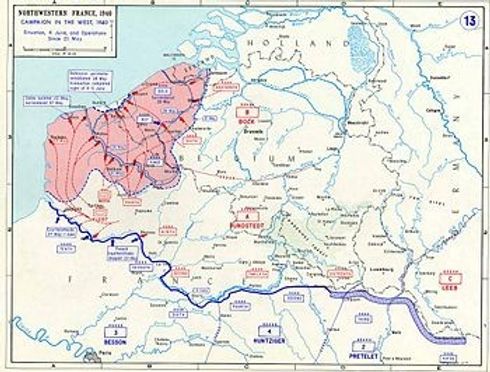

The situation on June 4, 1940, and actions was taken since May 21.

On May 20 French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud dismissed Maurice Gamelin for his failure to contain the German offensive and replaced him with Maxime Weygand. Weygand immediately attempted to devise new tactics to contain the Germans. His strategic task was more pressing however, so he formulated what was to be known as the Weygand Plan. He ordered his forces to pinch off the German armored spearhead by combining attacks from the north and the south. On the map this seemed like a feasible mission: the corridor through which von Kleist's two Panzer Corps had moved to the coast was a mere 40 kilometers (25 mi) wide. On paper Weygand had sufficient forces to execute it: in the north the three DLM and the BEF, in the south de Gaulle's 4th DCR. These units had an organic strength of about 1200 tanks, and the Panzer divisions were again very vulnerable, due to the rapidly deteriorating mechanical condition of their tanks. However, the condition of the Allied divisions was far worse. Both in the south and the north they could in reality muster only a handful of tanks. Nevertheless Weygand flew to Ypres on May 21 trying to convince the Belgians and the BEF of the soundness of his plan.

That same day, a detachment of the British Expeditionary Force under Major-General Harold Edward Franklyn had already attempted to at least delay the German offensive and, perhaps, to cut off the leading edge of the German army. The resulting Battle of Arras demonstrated the ability of the heavily armoured British Matilda tanks (the German 37 mm anti-tank guns proved ineffective against them) and the limited raid overran two German regiments. The panic that resulted (the German commander at Arras, Erwin Rommel, reported being attacked by 'hundreds' of tanks, though there were only 74 (+60 French) at the battle) temporarily delayed the German offensive. Rommel was forced to rely on 88 mm anti-aircraft and 105 mm field guns firing over open sights to halt these attacks. German reinforcements were able to press the British back to Vimy Ridge the following day.

Although this attack was not part of any coordinated attempt to destroy the Panzer Corps, the German High Command panicked even more than Rommel did. For the moment they feared that they had been ambushed. They thought that hundreds of Allied tanks were about to smash into their elite forces. However on the next day the German High Command had regained confidence and ordered Guderian's XIX Panzer Corps to press north and push into the Channel ports of Boulogne and Calais. This position was to the rear of the British and Allied forces to the north.

Also on May 22, the French tried to attack south to the east of Arras with a measure of infantry and tanks. However, by now the German infantry had begun to catch up, and the attack was, with some difficulty, stopped by the German 32nd Infantry Division.

The first rather weak attack from the south was launched on May 24 when 7th DIC, supported by a handful of tanks, failed to retake Amiens. On May 27 the incomplete British 1st Armoured Division, which had been hastily brought forward from Evrecy in Normandy where it was forming, attacked Abbeville in force but was beaten back with crippling losses. The next day de Gaulle tried again but with the same result, but by now even a complete success might not have saved the Allied forces to the north.