The Vietnam War

The Vietnam War, also known as the second Indochina war, was waged from 1954 to 1975, mainly between communist North Vietnam and South Vietnam being backed by the United States. North Vietnam forces included the North Vietnamese Army(NVA) and the infamous Viet Cong(VC), which were guerrilla fighters in the south. More than 3 million people were killed in the war, including over 58 000 Americans. More than half this number were Vietnamese civilians.

Roots of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War came about mostly due to the fall of the French Colonial Rule of the country. During WW2, when the Japanese invaded the country, political leader Ho Chi Minh rose to power. Inspired by communist China and the Soviet Union, he formed the Viet Minh or the League for the Independence of Vietnam.

After WW2, after the surrender of the Japanese and the collapse of the Japanese Empire, French Educated leader Emperor Bao immediately regained control. Ho Viet forces saw this as the perfect time to seize control. Ho Viet Minh forces then rose up, taking control over the city of Hanoi and electing Ho Chi Minh as their president. Ho Chi Minh declared his state s the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

Emperor Bao, seeing this, formed the state of Vietnam in July 1949 with the city of Saigon as its capital.

Both sides wanted the same thing - a unified Vietnam. But both sides had vastly different ideologies. The North wanted a communist regime, while the South wanted a political system modeled after western countries.

t

Emperor Bao

Ho Chi Minh

End of French colonial rule

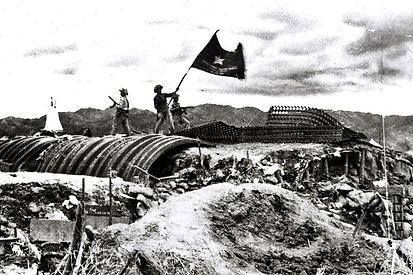

After communist forces took control over the north of the country, armed conflict began between the north and the south. This went on until a decisive battle at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954 ended in victory for northern Viet Minh forces. The French loss at the battle ended almost a century of French colonial rule in Indochina.

A treaty was then signed at the Geneva Convention, separating the 2 forces at the 17th parallel, with Ho in the north and Bao in the south.

In 1955 however, anti-communist politician Ngo Dinh Diem pushed Emperor Bao aside to become president of the Government of the Republic of Vietnam (GVN), often referred to during that era as South Vietnam

North Vietnam flag being placed at Dien Bien Phu, signifying the French's defeat

Position of 17th parallel

Ngo Dinh Diem

With the Cold War intensifying worldwide, the United States hardened its policies against any allies of the Soviet Union, and by 1955 President Dwight D. Eisenhower had pledged his firm support to Diem and South Vietnam.

With training and equipment from American military and the CIA, Diem’s security forces cracked down on Viet Minh sympathizers in the south, whom he derisively called Viet Cong (or Vietnamese Communist), arresting some 100,000 people, many of whom were brutally tortured and executed.

By 1957, the Viet Cong and other opponents of Diem’s repressive regime began fighting back with attacks on government officials and other targets, and by 1959 they had begun engaging the South Vietnamese army in firefights.

In December 1960, Diem’s many opponents within South Vietnam—both communist and non-communist—formed the National Liberation Front (NLF) to organize resistance to the regime. Though the NLF claimed to be autonomous and that most of its members were not communists, many in Washington assumed it was a puppet of Hanoi.

Build up of American forces

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy sent a team to South Korea to study the conditions there. The team came back and advised President Kennedy that they should start building up American military, economic and technical aid to help Diem hold back the North Vietnam forces.

Fearing the domino effect that more and more Asian countries would fall to communism, President Kennedy decides to take action. By 1962, there were some 9,000 American troops in Vietnam, compared to 800 during the 1950s.

US troops landing in Vietnam

At around this time, Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, were overthrown and killed in November 1963, just three weeks before President Kennedy's assassination.

The following instability in South Vietnam prompted President Lyndon B' Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to further increase U.S. military and economic support in South Vietnam.

To add fuel to the fire, two U.S. destroyers were attacked by North Vietnam torpedo boats in August of 1964. In retaliation, President Johnson ordered the bombing of military targets in North Vietnam. Congress then passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which allowed President Johnson full control of war powers. Soon the next year, Operation Rolling Thunder began, with U.S. planes conducting regular bombing raids.

In March 1965, President Johnson ordered some 86,000 troops to Vietnam. By the end of the year, military leaders were calling for another 175,000 troops. Despite the risk of war escalation, President Johnson ordered 100,000 troops into Vietnam by the end of 1965, and another 100,000 at the start of 1966.

In addition to the United States, South Korea, Thailand, Australia and New Zealand also committed troops to fight in South Vietnam (albeit on a much smaller scale).

In contrast to the air attacks on North Vietnam, the U.S.-South Vietnamese war effort in the south was fought primarily on the ground, largely under the command of General William Westmoreland, in coordination with the government of General Nguyen Van Thieu in Saigon.

Westmoreland pursued a policy of attrition, aiming to kill as many enemy troops as possible rather than trying to secure territory. By 1966, large areas of South Vietnam had been designated as “free-fire zones,” from which all innocent civilians were supposed to have evacuated and only enemy remained. Heavy bombing by B-52 aircraft or shelling made these zones uninhabitable, as refugees poured into camps in designated safe areas near Saigon and other cities.

Even as the enemy body count (at times exaggerated by U.S. and South Vietnamese authorities) mounted steadily, DRV and Viet Cong troops refused to stop fighting, encouraged by the fact that they could easily reoccupy lost territory with manpower and supplies delivered via the Ho Chi Minh Trailthrough Cambodia and Laos. Additionally, supported by aid from China and the Soviet Union, North Vietnam strengthened its air defenses.

Protestors outside the Pentagon

Vietnam War protests

By 1967, American casualties have reached over 15,000, and over 100,000 others were wounded. As the war stretched on, American troops began to mistrust the American government, despite multiple claims from Washington that the war was being won. As the years went on, physical and psychological states of the soldiers began to deteriorate. More and more soldiers resorted to drugs, and many more were suffering from PTSD. Mutinies became more and more common, and attacks were committed against officers and Non-Commissioner officers.

Americans at home were turning their backs on the war as well, horrified as they see the gruesome images of the war on their television. On October of 1967, as many as 35,000 protestors gathered outside the Pentagon, demanding soldiers to be sent home. They claimed that civilians, not enemy combatants were targeted in the war, and that the United States Government was supporting a corrupted regime in Saigon.

Tet Offensive

By the end of 1967, Hanoi's leadership was getting impatient at the seeming lack of progress in the war, and sought for an operation that would lead the United States to give up on the world.

On the morning of 31st January 1968, the Tet offensive was launched, with more than 80,000 DRV soldiers storming into more than a 100 cities and towns in South Vietnam almost simultaneously. American and South Korean forces were initially taken aback and lost control of these towns. However, they recovered quickly and immediately launched a retaliatory strike. Soon, most of the towns were in American hands again. None of the towns were held by the DRZ for more than 2 days.

The Tet offensive stunned the public, but William Westmoreland had requested for another 200,000 troops, despite reassurances that they were winning. This caused President Johnson's approval rating to drop. President Johnson then called for a halt of bombings in Northen Vietnam and promised to try and conduct peace talks.

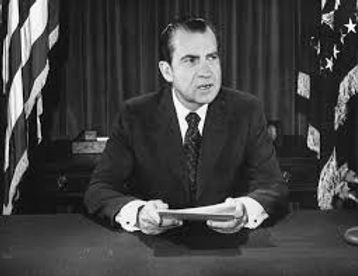

President Johnson laid out his new tactic in a March 1968 speech, met with a positive response from Hanoi, and peace talks between the U.S. and North Vietnam opened in Paris that May. Despite the later inclusion of the South Vietnamese and the NLF, the dialogue soon reached an impasse, and after a bitter 1968 election season marred by violence, Republican Richard M. Nixon won the presidency.

Map showing Tet offensive.

Vietnamnization

President Nixon sought to deflate the anti-war movement by appealing to a “silent majority” of Americans who he believed supported the war effort. In an attempt to limit the volume of American casualties, he announced a program called Vietnamization: withdrawing U.S. troops, increasing aerial and artillery bombardment and giving the South Vietnamese the training and weapons needed to effectively control the ground war.

In addition to this Vietnamization policy, Nixon continued public peace talks in Paris, adding higher-level secret talks conducted by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger beginning in the spring of 1968.

The North Vietnamese continued to insist on complete and unconditional U.S. withdrawal—plus the ouster of U.S.-backed General Nguyen Van Thieu—as conditions of peace, however, and as a result the peace talks stalled.

In 1970, American and South Vietnam troops invaded Cambodia, hoping to destroy DRZ bases there. South Vietnam immediately followed with their own offensive of Laos, which was pushed back by North Vietnam.

By the end of June 1972, however, after a failed offensive into South Vietnam, Hanoi was finally willing to compromise. Kissinger and North Vietnamese representatives drafted a peace agreement by early fall, but leaders in Saigon rejected it, and in December Nixon authorized a number of bombing raids against targets in Hanoi and Haiphong. Known as the Christmas Bombings, the raids drew international condemnation.

End of the war.

In January 1973, the United States and North Vietnam concluded a final peace agreement, ending open hostilities between the two nations. War between North and South Vietnam continued, however, until April 30, 1975, when DRV forces captured Saigon, renaming it Ho Chi Minh City (Ho himself died in 1969).

More than two decades of violent conflict had inflicted a devastating toll on Vietnam’s population: After years of warfare, an estimated 2 million Vietnamese were killed, while 3 million were wounded and another 12 million became refugees. Warfare had demolished the country’s infrastructure and economy, and reconstruction proceeded slowly.

In 1976, Vietnam was unified as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, though sporadic violence continued over the next 15 years, including conflicts with neighboring China and Cambodia. Under a broad free market policy put in place in 1986, the economy began to improve, boosted by oil export revenues and an influx of foreign capital. Trade and diplomatic relations between Vietnam and the U.S. resumed in the 1990s.

In the United States, the effects of the Vietnam War would linger long after the last troops returned home in 1973. The nation spent more than $120 billion on the conflict in Vietnam from 1965-73; this massive spending led to widespread inflation, exacerbated by a worldwide oil crisis in 1973 and skyrocketing fuel prices.

Psychologically, the effects ran even deeper. The war had pierced the myth of American invincibility and had bitterly divided the nation. Many returning veterans faced negative reactions from both opponents of the war (who viewed them as having killed innocent civilians) and its supporters (who saw them as having lost the war), along with physical damage including the effects of exposure to the toxic herbicide Agent Orange, millions of gallons of which had been dumped by U.S. planes on the dense forests of Vietnam.

In 1982, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was unveiled in Washington, D.C. On it were inscribed the names of 57,939 American men and women killed or missing in the war; later additions brought that total to 58,200.