Nirvelle Offensive

Nivelle, who had replaced Joseph Joffre in December 1915 as head of all French forces, had tenaciously argued for a major spring offensive in spite of powerful opposition in the French government, at one point threatening to resign if the offensive did not go ahead. He was convinced that by implementing the tactics he had used to considerable success at Verdun during the French counter-attacks in the fall of 1916, on a greater scale, the Allies could achieve a breakthrough on the Western Front within 48 hours. In preparation for the planned offensive at the Aisne River, the British army began its attacks on April 9 around the town of Arras, capital of the Artois region of France, with the limited objective of pulling German reserve troops away from the Aisne, where the French would launch the central thrust of the offensive.

Nivelle Joseph Joffre

Of the nearly 1,000 heavy guns used in the attacks, 377 were aimed at a six-kilometer stretch of front-facing Vimy Ridge, a high point overlooking the plains of Artois, France, to the east. The Canadian Corps was given the task of moving forward to capture the ridge itself, directed by photographic images taken by aerial reconnaissance crafts used to plan the attacks as well as to report progress during their execution. After overcoming 4,000 yards of German defenses, the Canadians captured Vimy Ridge on April 12—a national triumph for Canada and a successful outcome for the initial phase of the Nivelle Offensive, as the Germans were forced to double their strength in the Arras region and thus draw forces away from the area further south, where Nivelle was preparing to launch his attacks.

Tactics used

On April 16, Nivelle and the French began their assault along an 80-kilometer front stretching from Soissons to Reims along the Aisne River. Despite the evacuation of reserve troops to Arras, the German positions were deeply and strongly entrenched in the region, which they had occupied since September 1914. The Germans had ample warning of French intentions from their intelligence systems; this, combined with the depth of their positions, meant that the Allies were literally outgunned from the beginning of the battle. The overconfident Nivelle had ordered a rate of advance of up to two kilometers per hour, which proved exceedingly difficult with the steep grade of the land, horrible weather and the strength of enemy fire.

.For this attack, known as the Second Battle of the Aisne, the French used tanks in great numbers for the first time; by the end of the first day, however, 57 of 132 tanks had been destroyed and 64 more had become bogged down in the mud. All in all, the French suffered 40,000 casualties on April 16 alone, a loss comparable to that suffered by the British on the first day of the Battle of the Somme offensive of July 1, 1916. It was clear from the start that the attack had failed to achieve the decisive breakthrough Nivelle had planned: over the next three days, the French made only modest gains, advancing up to seven kilometers on the west of the front and taking 20,000 German prisoners. On the rest of the front, progress was significantly slower, and Nivelle was forced to call off the attacks on April 20. The high casualty rate among French forces during the ill-fated Nivelle Offensive, combined with the continuing effects of exhausting battles at Verdun and the Somme, led to sharply increased discontent among the soldiers on the Western Front. Mutinies began in late April 1917, and by June had affected 68 divisions, or about 40,000 troops. The army’s response to this was quick: on April 25, Nivelle was dismissed as commander in chief.

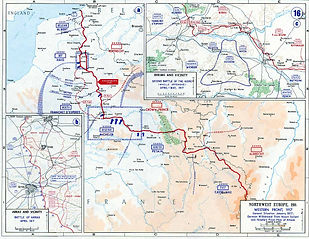

Nivelle’s plan seemed sound according to military theory. The front lines had shifted gradually over the previous two years, resulting in an interlocking series of bulges, or salients, on both sides. Salients are dangerous for a defender, because the attacker can surround the defender on three sides. In the context of the fighting in World War I, this also means more ground on which to site heavy artillery for the attack. Both sides had salients all along the front lines, but in general, the Germans remained on the defensive in the west, and so the Germans faced greater peril from these salients. The largest salient was the one that ran from the river Somme, where French and British forces met, to the river Oise in the south, and then southeast along the Aisne Canal. It was large enough to accommodate a massive build-up of forces, and conveniently, it permitted the British to provide substantial aid with a reduced risk.

The principal effort was to be in the south, along the Aisne Canal, where a road called the Chemin des Dames extended northeast from Soissons and turned east into German-held territory. Four fresh armies, organized as the Reserve Army Group, were tasked for this part of the effort. The British, striking east from their own salient around the city of Arras, were to provide the initial diversion that gave the Reserve Army Group a chance to surprise the Germans, while the French Northern Army Group, positioned between the Somme and Oise rivers, would subsequently attack their section of the front. This was to be accomplished with the same level of cooperation between the artillery and the infantry that had brought great success at Verdun, now expanded to a far greater scale. The first problem with the plan was the fact that the Germans were just as aware of their vulnerability as the Entente leadership was. All winter they had been hard at work in rectifying this weakness. The French and British had more men and more supplies than the Germans, who were then suffering the beginning of their third year of the blockade.

The Germans sought new efficiencies in their defensive positions, preparing a new defensive line deeper in occupied French territory. Called the Siegfried Line by the Germans, but later to be known as the Hindenburg Line among the western Allies, this new trench system was to be far stronger than the existing lines, which had been constructed within sight of the enemy, sometimes under hasty circumstances. Moreover, pulling back to the Siegfried Line would give the Germans 25 fewer miles to defend, enabling as many as thirteen divisions to pull back from trench duty, giving the Germans a substantial pool of men for offensive action or support duties in the future. Operation Alberich, a withdrawal to the Siegfried Line accompanied by the implementation of a scorched-earth policy in the territory being abandoned, started on March 16. The second problem was the failure of the Entente commanders to respond to the change in circumstances in an adequate manner. In fact, they failed to notice the German withdrawal until March 25. Once this was noticed, British and French forces advanced gingerly in the Germans’ wake. Much of their planning had been invalidated at a stroke

In the end, the allied operation failed terribly. Shortly after the attack began, the Germans succeeded in asserting air superiority, and the French artillery was effectively rendered blind. In spite of Nivelle’s promises that his attack would not become like the Verdun or Somme battles, the offensive descended into a bloody quagmire on the first day. The French air assets failed to give the artillery the battlefield intelligence it needed. The artillery failed to give the infantry the support it needed, and French soldiers faced well-prepared defenders instead of dazed stragglers. The tanks that were gathered for the attack failed even to make contact with the enemy. French losses reached 40,000 in a single day, with only negligible gains in terms of compensation. Nivelle persevered for another three days, trying to revive his offensive until the 20th, by which time it was clear that it had failed. The offensive was called off, but it took until May 7 for the French to completely extricate themselves from the fighting, during which time French casualties exceeded 130,000.

The British were obligated to begin another supporting attack at Arras on April 23, just to give the French some cover for their retreat. While the British ended the offensive with control over Vimy Ridge, their own casualties approached 150,000. It was the French, however, who were more adversely affected by the loss. The French Army had believed in the offensive, regardless of what top commanders might have thought, and when it had proven a colossal failure, the army was disillusioned as thoroughly as it had been inspired beforehand. Throughout the summer of 1917, the French Army was paralyzed by mutinies that threatened to end its cohesiveness altogether. Nivelle was reassigned to North Africa on May 15, with supreme command passing to generals Petain and Foch. While the French Army struggled to reassert itself, the Entente war effort was left mainly in the hands of the British. The Nivelle Offensive was perhaps the most disastrous single offensive in the war.