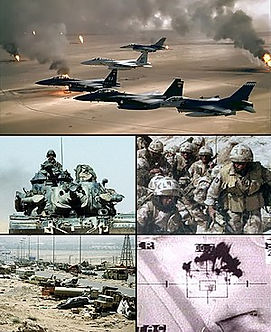

Persian Gulf War

The Persian Gulf War, also known as also known under other names, such as the Persian Gulf War, First Gulf War, Gulf War I, Kuwait War, First Iraq War or Iraq War, took place from 2 August 1990 to 28 February 1991, as a direct result of Saddam Hussein’s refusal to withdraw his troops from Kuwait. The war was waged between a coalition force from 35 other countries led by the US, and Iraq. The war encompassed 2 major operations-Operation Desert Shield, and Operation Desert Storm, an air coalition led to destroy key Iraqi military bases and facilities. The war ended when a ground coalition pushed the Iraqi forces back beyond their original border, and 100 hours after the start of the ground coalition, a ceasefire was called.

Origins

Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein ordered the invasion and occupation of neighboring Kuwait in early August 1990. Alarmed by these actions, fellow Arab powers such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt called on the United States and other Western nations to intervene. Hussein defied United Nations Security Council demands to withdraw from Kuwait by mid-January 1991, and the Persian Gulf War began with a massive U.S.-led air offensive known as Operation Desert Storm. After 42 days of relentless attacks by the allied coalition in the air and on the ground, U.S. President George H.W. Bush declared a cease-fire on February 28; by that time, most Iraqi forces in Kuwait had either surrendered or fled. Though the Persian Gulf War was initially considered an unqualified success for the international coalition, simmering conflict in the troubled region led to a second Gulf War–known as the Iraq War–that began in 2003.

Though the long-running war between Iran and Iraq had ended in a United Nations-brokered ceasefire in August 1988, by mid-1990 the two states had yet to begin negotiating a permanent peace treaty. When their foreign ministers met in Geneva that July, prospects for peace suddenly seemed bright, as it appeared that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein was prepared to dissolve that conflict and return territory that his forces had long occupied. Two weeks later, however, Hussein delivered a speech in which he accused neighboring nation Kuwait of siphoning crude oil from the Ar-Rumaylah oil fields located along their common border. He insisted that Kuwait and Saudi Arabia and cancel out $30 billion of Iraq’s foreign debt, and accused them of conspiring to keep oil prices low in an effort to pander to Western oil-buying nations.

In addition to Hussein’s incendiary speech, Iraq had begun amassing troops on Kuwait’s border. Alarmed by these actions, President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt initiated negotiations between Iraq and Kuwait in an effort to avoid intervention by the United States or other powers from outside the Gulf region. Hussein broke off the negotiations after only two hours, and on August 2, 1990 ordered the invasion of Kuwait. Hussein’s assumption that his fellow Arab states would stand by in the face of his invasion of Kuwait, and not call in outside help to stop it, proved to be a miscalculation. Two-thirds of the 21 members of the Arab League condemned Iraq’s act of aggression, and Saudi Arabia’s King Fahd, along with Kuwait’s government-in-exile, turned to the United States and other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for support.

Iraqi invasion of Kuwait

U.S. President George H.W. Bush immediately condemned the invasion, as did the governments of Britain and the Soviet Union. On August 3, the United Nations Security Council called for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait; three days later, King Fahd met with U.S. Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney to request U.S. military assistance. On August 8, the day on which the Iraqi government formally annexed Kuwait–Hussein called it Iraq’s “19th province”–the first U.S. Air Force fighter planes began arriving in Saudi Arabia as part of a military buildup dubbed Operation Desert Shield. The planes were accompanied by troops sent by NATO allies as well as Egypt and several other Arab nations, designed to guard against a possible Iraqi attack on Saudi Arabia.

In Kuwait, Iraq increased its occupation forces to some 300,000 troops. In an effort to garner support from the Muslim world, Hussein declared a jihad, or holy war, against the coalition; he also attempted to ally himself with the Palestinian cause by offering to evacuate Kuwait in return for an Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories. When these efforts failed, Hussein concluded a hasty peace with Iran so as to bring his army up to full strength.

Gulf War begins

On November 29, 1990, the U.N. Security Council authorized the use of “all necessary means” of force against Iraq if it did not withdraw from Kuwait by the following January 15. By January, the coalition forces prepared to face off against Iraq numbered some 750,000, including 540,000 U.S. personnel and smaller forces from Britain, France, Germany, the Soviet Union, Japan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, among other nations. Iraq, for its part, had the support of Jordan (another vulnerable neighbor), Algeria, the Sudan, Yemen, Tunisia and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).

On 17 January 1991, Operation Desert Storm began. It involved an air attack led by the US on Iraqi defences, military targets and oil refineries. The operation lasted for 38 days, after which the Iraqi air force and ground forces were effectively crippled.

On 24 February, Operation Desert Sabre began. Ground forces advanced from North Western Saudi Arabia into Iraqi occupied Kuwait. Over the next four days, coalition forces encircled and defeated the Iraqis and liberated Kuwait. At the same time, U.S. forces stormed into Iraq some 120 miles west of Kuwait, attacking Iraq’s armored reserves from the rear. The elite Iraqi Republican Guard mounted a defense south of Al-Basrah in southeastern Iraq, but most were defeated by February 27.

With Iraqi resistance nearing collapse, Bush declared a ceasefire on February 28, ending the Persian Gulf War. According to the peace terms that Hussein subsequently accepted, Iraq would recognize Kuwait’s sovereignty and get rid of all its weapons of mass destruction (including nuclear, biological and chemical weapons). In all, an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 Iraqi forces were killed, in comparison with only 300 coalition troops.

Aftermath

Though the Gulf War was recognized as a decisive victory for the coalition, Kuwait and Iraq suffered enormous damage, and Saddam Hussein was not forced from power. Intended by coalition leaders to be a “limited” war fought at minimum cost, it would have lingering effects for years to come, both in the Persian Gulf region and around the world. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Hussein’s forces brutally suppressed uprisings by Kurds in the north of Iraq and Shi’ites in the south. The United States-led coalition failed to support the uprisings, afraid that the Iraqi state would be dissolved if they succeeded.In the years that followed, U.S. and British aircraft continued to patrol skies and mandate a no-fly zone over Iraq, while Iraqi authorities made every effort to frustrate the carrying out of the peace terms, especially United Nations weapons inspections. This resulted in a brief resumption of hostilities in 1998, after which Iraq steadfastly refused to admit weapons inspectors. In addition, Iraqi force regularly exchanged fire with U.S. and British aircraft over the no-fly zone.

In 2002, the United States (now led by President George W. Bush, son of the former president) sponsored a new U.N. resolution calling for the return of weapons inspectors to Iraq; U.N. inspectors reentered Iraq that November. Amid differences between Security Council member states over how well Iraq had complied with those inspections, the United States and Britain began amassing forces on Iraq’s border. Bush (without further U.N. approval) issued an ultimatum on March 17, 2003, demanding that Saddam Hussein step down from power and leave Iraq within 48 hours, under threat of war. Hussein refused, and the second Persian Gulf War–more generally known as the Iraq War–began three days later.

Operation Desert Storm

On January 16, 1991, President George H. W. Bush announced the start of what would be called Operation Desert Storm—a military operation to expel occupying Iraqi forces from Kuwait, which Iraq had invaded and annexed months earlier. For weeks, a U.S.-led coalition of two dozen nations had positioned more than 900,000 troops in the region, most stationed on the Saudi-Iraq border. A U.N.-declared deadline for withdrawal passed on January 15, with no action from Iraq, so coalition forces began a five-week bombardment of Iraqi command and control targets from air and sea.

On the morning of January 1991, an American Strike package spearheaded by F 15 Eagles and a F111 electronic attack aircraft started the bombardment. Over the next 38 days, American forces would inflict heavy damage to the Iraqis while sustaining little to no damage. A new form of aerial warfare was waged, brought along by new technology such as “smart” radio guided bombs, beyond visual range missiles, and sophisticated anti air missile systems. F 15 eagles will face off against Soviet Mig 23s, MiG 25s and MiG 29s. The revolutionary aircraft would prove its worth by claiming 39 aircraft, while losing none to combat losses.

French involvement in the war

Operation Daguet

Soon after the invasion of Kuwait, the French sent a frigate to reinforce the other 2 French ships that were already in the gulf. Operation "Salamandre" launched with the deployment of the 5th Regiment of Combat Helicopters (RHC) and a company of the first Regiment of Infantry on board the French aircraft carrier Clemenceau, escorted by the cruiser Colbert the tanker Var and the tugboat A696 Buffle.

On 14 September 1990, Iraqi forces entered the residence of the French ambassador in Kuwait. The French responded by increasing military action in the area. By now, Operation Salamander was renamed Operation Daguet, commanded by General Michel Roquejoffre. French reinforcements began to arrive in late 1990 and early 1991.

The French’s ground forces were mainly made out of the Daguet Division. Units were drawn from the 6th light armoured division, 2nd Armoured division and the French Foreign legion. The forces were divided into 2 task forces, Groupement ouest and Groupement est. Initially the French operated independently, but further into the war the division was placed under the US XVIII Airborne Corp.

The role of the 6th French Light Armoured Division and the US XVIII Airborne Corps was to protect the theatre left flank and perhaps draw off Iraqi tactical and operational reserves.

The landing platform ship Foudre was sent to Kuwait to increase the force's medical capabilities.

The naval part of the operation was called "Opération Artimon". From August, it was carried out by three A 69 type avisos, organised around the frigates Dupleix and Montcalm, supported by the tanker Durance. In October, the deployment was reinforced with the frigate Lamotte-Picquet and fleet escort Du Chayla.

In December, Jean de Vienne and Premier maître l'Her replaced Lamotte-Picquet. In March Jean de Vienne was relieved by Latouche-Tréville.

The ships enforced the embargo against Iraq by controlling merchant shipping, including 28 586 controls and the boarding of over 1000 ships for further inspection. 14 warning shots were fired. Notably, on 20 September, the Iraqi ship AlTaawin Al Aradien was intercepted by the cruiser USS San Jacinto, the Spanish frigate Infanta Cristina and the fleet escort Du Chayla; she refused to comply until warning shots were fired, but refused to be boarded by anyone but the French. A group of Fusiliers Marins hence inspected the ship.

A long series of UN Security Council resolutions were passed regarding the conflict. One of the most important was Resolution 678, passed on 29 November giving Iraq a withdrawal deadline of 15 January 1991, and authorizing "all necessary means to uphold and implement Resolution 660", a diplomatic formulation authorising the use of force. After the deadline passed, on 17 January 1991, intensive air operations began. The majority of missions were flown by the United States, but French Air Force aircraft also took part. SEPECAT Jaguars undertook ground attack missions, Mirage F1s undertook ground attack and reconnaissance missions and Mirage 2000s provided fighter air cover. Mirage F1s were later grounded over concerns that they would be misidentified as enemy fighters by coalition forces since the Iraqi Air Force also operated the Mirage F1.

Compared to the US and UK, the French suffered no aircraft losses.

On 24 February 1991, the ground phase began. Reconnaissance units of the 6th French Light Armoured Division advanced into Iraq. Three hours later, the French main body attacked. The initial objective for the French was an airfield 90 miles (140 km) inside Iraq at As-Salman. Reinforced by the 325th Airborne Infantry Regiment[5] from the US 82nd Airborne Division, the French crossed the border unopposed and attacked north. The French then came across elements of the 45th Iraqi Mechanised Infantry Division. After a brief battle, supported by French Army missile-armed Aérospatiale Gazelle attack helicopters, they controlled the objective and captured 2,500 prisoners. By the end of the first day, the French 6th Light Armoured Division, supported by the 82nd Airborne Division had secured its objectives and continued the attack north, securing the highways from Baghdad to southern Iraq.

Technology used during the war

Radio and laser guided bombs

For the first time in history, radio and laser guided bombs have played a huge role in a war. With help from this new weapon, the US and its allies effectively crippled the 4th largest army in the world (at that time) while sustaining vey little losses.

The basic concept of a bomb could hardly be simpler. A conventional bomb consists of some explosive material packed into a sturdy case with a fuze mechanism. The fuze mechanism has a triggering device, typically a time-delay system, an impact sensor or a target-proximity sensor, which sets the bomb off. When the trigger goes off, the fuze ignites the explosive material, resulting in an explosion. The extreme pressure and flying debris of the explosion destroys surrounding structures

Bombs which only contain the above components are known as “dumb bombs” called so because they simply fall to the ground without steering itself. These bombs have been used for a long time-WW1, WW2, the Korean War, Vietnam War, and even now, the venerable American B2 bomber also uses such “dumb bombs”.

"Smart bombs," by contrast, control their fall precisely in order to hit a designated target dead on.

A “smart bomb” contains all the components of a “dumb bomb” with a few additions. It has an electronic sensor system, a built-in control system (an onboard computer), a set of adjustable flight fins and a battery.

When a plane drops a guided bomb, it practically becomes a glider. Even though it does not have its own propulsion, like a missile does, its initial propulsion is caused by the bomb dropping (inertia caused when the plane drops the bomb). After which its own sets of fins will guide it towards its target. The target is tracked by the bomb’s sensor and control system. The sensor system feeds the control system the relative position of the target, and the control system processes this information and figures out how the bomb should turn to steer toward the target. This ensures pinpoint accuracy, which is essential as many targets during the gulf war require precision bombing, something that is very difficult to do with a “dumb bomb”.

Guided bombs have different ways in which they were guided. The 2 main ways are by TV/IR-guided(Radio guided) and laser guided.

TV/IR has a conventional television video camera or an infrared camera (for night vision) mounted to its nose. In remote control mode, a bombardier (on board a plane/bomber) will man control over the bomb. The remote operator relays commands to the control system to steer the bomb through the air -- the bomb acts something like a remote-control plane. In this mode, the operator may launch the bomb without a specific target and sight, and then pick up the target from the video as the bomb gets closer to the ground.

In automatic mode, the pilot locates a target through the bomb's video camera prior to launch and sends a signal to the bomb telling it to lock on to the target. The bomb's control system steers the bomb so that the indicated target image always stays near the center of the video display. In this way, the bomb zeros in on the locked target automatically.

Another way in which a bomb is control is via laser. Instead of a camera or video receiver, it instead has an array of photodiodes - to pick up laser trails. Different bombs have photodiodes to pick up different arrays of lasers. Now instead of an operator controlling a bomb via radio, or locking on the bomb via a video camera, the targeter now locks on a target for the bomb by “painting” it with a laser. The bomb’s photodiodes then pick up the laser, and similar to the radio controlled bomb, the bomb control system steers the bomb so that it stays on track with where the laser is at.

Both of these systems can be highly effective, but they have one major drawback: The bomb sensor has to maintain visual contact with the target. If cloud cover or obstacles get in the way, the bomb will most likely veer off course.

Nowaday guided bombs are usually Joint Direct Attack Munition(JDAM) bombs with GPS receivers. In layman terms, the bomb is able to detect itself from space using the GPS, as well as the target. This way, the bomb can direct itself to the target without need for the target to be in visual range.

4th generation fighter jets

The Gulf war saw an extensive use of aircraft, especially by the allies during Operation Desert Storm. The Gulf War was the second time 4th generation fighter aircraft were widely deployed, the first being the Iran Iraq war of 1980-1988. 4th Generation fighter aircraft usually refer to aircraft being used from the 1980s to the present day, and was heavily influenced by designs from the 1970s.

4th Generation aircraft designs were influenced by the lessons learnt from 3rd generation aircraft designs. Previously, the development of missiles led to the mindset that Within Visual Range(WVR) combat would be rendered obsolete. However, this was not true as early missiles were unreliable and would still require a pilot to visually identify a target before he was able to fire his missiles. Hence, interceptor aircraft designs, which were so heavily emphasised in 3rd generation aircraft, was now relegated to a secondary role in the 4th generation aircraft design.

Maneuverability is now the priority of the day. Maneuverability of 4th generation aircraft was vastly improved. This was made possible due to made possible by introduction of the fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control system (FLCS), which in turn was possible due to advances in digital computers and system-integration techniques. Avionic technology would later play a huge role as analog systems are gradually replaced by electronic ones starting in the late 1980s. The further advance of microcomputers in the 1980s and 1990s permitted rapid upgrades to the avionics over the lifetimes of these fighters, incorporating system upgrades such as active electronically scanned array (AESA), digital avionics buses and infra-red search and track (IRST).

Later on, 4th generation aircraft designs that were upgraded with improved avionics of the present day, or were influenced by more modern designs will be known as 4.5 generation aircraft. These aircraft represented intended to reflect a class of fighters that are evolutionary upgrades of the 4th generation incorporating integrated avionics suites, advanced weapons efforts to make the (mostly) conventionally designed aircraft nonetheless less easily detectable and trackable as a response to advancing missile and radar technology.

Fly by wire technology.

One of the new innovations on fourth generation jet fighters is fly-by-wire

The YF-16, eventually developed into the F-16 Fighting Falcon, was the world’s first aircraft intentionally designed to be slightly aerodynamically unstable. This technique, called "relaxed static stability" (RSS), was incorporated to further enhance the aircraft’s performance. Most aircraft are designed with positive static stability, which induces an aircraft to return to its original attitude following a disturbance. However, positive static stability, the tendency to remain in its current attitude, opposes the pilot’s efforts to maneuver. On the other hand, an aircraft with negative static stability will, in the absence of control input, readily deviate from level and controlled flight.

An aircraft with negative static stability can therefore be made more maneuverable. At supersonic airspeed, a negatively stable aircraft can exhibit positive static stability due to aerodynamic center migration.[1][6] To counter this tendency to depart from controlled flight—and avoid the need for constant minute trimming inputs by the pilot—the 4th gen aircraft has a quadruplex (four-channel) fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control system (FLCS). The flight control computer (FLCC), which is the key component of the FLCS, accepts the pilot’s input from the stick and rudder controls, and manipulates the control surfaces in such a way as to produce the desired result without inducing a loss of control. The FLCC also takes thousands of measurements per second of the aircraft’s attitude, and automatically makes corrections to counter deviations from the flight path that were not input by the pilot. Coordinated turn is also achieved in the same way, processing thousands of instructions per second to synchronize yawing and rolling to minimize sideslip drag in turns.

Thrust Vectoring

Thrust Vectoring is a way in which the maneuverability of an aircraft can be enhanced, first introduced by Soviet Aircraft. This is done by enabling the nozzles, or exhausts of an engine to be able to move independently, directing thrust where needed. This translates to having more directional maneuverability, as thrust vectoring is able to direct the engine’s power into directional changes more effectively than using a plane’s control surfaces.

Pioneered by the Soviets, the Sukhoi SU 27 was the first ever aircraft to efficiently perform the Pugachev's Cobra, a maneuver where the aircraft was near zero-speed while having a high angle of attack, while still maintaining the altitude.

Supercruise

Supercruise is the ability of aircraft to cruise at supersonic speeds without the afterburner.

Because of parasitic drag effects, fighters carrying external weapons stores encounter a vastly increased drag divergence near the speed of sound. This can prevent safe acceleration through the transonic regime or make it too fuel-expensive to be effective on missions. Meanwhile, maintaining supersonic speed without (periodic) afterburner use saves large quantities of fuel too, increasing the range at which an aircraft can in reality still take advantage of its full performance.

Avionics

Avionics is a catch-all term for the electronic systems aboard an aircraft, which have been growing in complexity and importance. The main elements of an aircraft's avionics are its communication and navigation systems, sensors (radar and IR), computers and data bus, and user interface. Because they can be readily swapped out as new technologies become available, they are often upgraded over the lifetime of an aircraft. A number of F-15C Eagles, the type was first produced in 1978, have received upgrades in the 2007 such as AESA radar and Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing Systemand will receive the 2040C Eagle upgrade to keep them in service until 2040, thanks to its large size and long airframe life.

Details about these systems are highly classified. Thus, many export aircraft have downgraded avionics, and buyers often replace them with domestically developed avionics, sometimes considered superior to the original. Examples are the Sukhoi Su-30MKI sold to India, the F-15I and F-16I sold to Israel, and the F-15K sold to South Korea.

The primary sensor for all modern fighters is radar. The U.S. fielded its first modified F-15Cs equipped with AN/APG-63(V)2 Active electronically scanned array radars,[15] which have no moving parts and are capable of projecting a much tighter beam and quicker scans. Later on, it was introduced to the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and the block 60 (export) F-16 also, and will be used for future American fighters. France introduced its first indigenous AESA radar, the RBE2-AESA built by Thales in February 2012[16] for use on the Rafale. The RBE2-AESA can also be retrofitted on the Mirage 2000. A European consortium GTDAR is developing an AESA Euroradar CAPTOR radar for future use on the Typhoon. Russia has an AESA radar on its MIG-35 and their newest Su-27 versions. For the next-generation F-22 and F-35, the U.S. will use low probability of intercept (LPI) capacity. This will spread the energy of a radar pulse over several frequencies, so as not to trip the radar warning receivers that all aircraft carry.

In response to the increasing American emphasis on radar-evading stealth designs, Russia turned to alternate sensors, with emphasis on infra-red search and track (IRST) sensors, first introduced on the American F-101 Voodoo and F-102 Delta Dagger fighters in the 1960s, for detection and tracking of airborne targets. These measure IR radiation from targets. As a passive sensor, it has limited range, and contains no inherent data about position and direction of targets - these must be inferred from the images captured. To offset this, IRST systems can incorporate a laser rangefinder in order to provide full fire-control solutions for cannon fire or for launching missiles. Using this method, German MiG-29 using helmet-displayed IRST systems were able to acquire a missile lock with greater efficiency than USAF F-16 in wargame exercises. IRST sensors have now become standard on Russian aircraft. With the exception of the F-14D (officially retired as of September 2006), no 4th-generation Western fighters carry built-in IRST sensors for air-to-air detection, though the similar FLIR is often used to acquire ground targets.

However '4.5 generation' fighters started introducing integrated IRST systems, such as the Dassault Rafale boasting the Optronique secteur frontal integrated IRST, a feature adopted very early in its design as an "omnirole" fighter jet. The Eurofighter Typhoon introduced the PIRATE-IRST (beginning with Tranche 1 Block 5 aircraft,[17] while previously build aircraft are being retrofited since spring 2007[18]) and the F-35s will have built-in, PIRATE-IRST sensors, a feature adopted early in the design, meanwhile beginning in 2012 the Super Hornet will also have an IRST.

The tactical implications of the computing and data bus capabilities of aircraft are hard to determine. A more sophisticated computer bus would allow more flexible uses of the existing avionics. For example, it is speculated that the F-22 is able to jam or damage enemy electronics with a focused application of its radar. A computing feature of significant tactical importance is the datalink. All modern European and American aircraft are capable of sharing targeting data with allied fighters and AWACS planes (see JTIDS). The Russian MiG-31 interceptor also has some datalink capability, so it is reasonable to assume that other Russian planes can also do so. The sharing of targeting and sensor data allows pilots to put radiating, highly visible sensors further from enemy forces, while using that data to vector silent fighters toward the enemy.

Electronic warfare

Electronic Warfare is military action or operations involving the electromagnetic spectrum. This includes Electronic attack and Electronic Warfare Support. Electronic Attack is the destruction of an enemies electronic-warfare capabilities, such as his radar systems and communications. Aircraft that do these are often modified from existing models, and use sophisticated technology to aid their efforts. These aircraft include the EF-4G Wild Weasel. Electronic Warfare Support is the interception and location of electromagnetic energy given off by enemy systems. Aircraft that do this job can also be classified as reconnaissance aircraft. These aircraft include the EC-130H Compass Call.

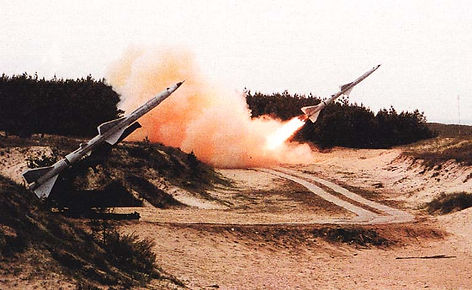

The Iraqi forces have placed overlapping short and long range SAMs and AAA, backed up with powerful radar stations. This formed an impenetrable line of defence such that no aircraft could enter the airspace without facing a multitude of weapons facing it at once.

A typical composition for the Soviet PVO model would see static area defences implemented with batteries of SA-2 and SA-3, with mobile area defences and gaps in static defensive coverage plugged with the PVO-SV SA-6. The area defences would be supported by early warning radars at key sites, these covered redundantly by the early warning and acquisition radars of the SAM batteries.

Point defences would then be comprised of mixed batteries, clustered about the specific target to be defended. A typical structure for a point defence battery is a quartet of SA-9 or SA-13 SAM systems, complemented by a quartet of ZSU-23-4P mobile AAA systems. These would then be supplemented by singletons, pairs or quartets of the mobile, fully self-contained SA-8/Land Roll or Roland command link SAMs

Hence, operation Desert Storm was spearheaded by electronic warfare aircraft, most famous is the F111 Raven, backed up by an umbrella of F 15 fighter jets. In the morning on 17 January 1991, an F111 jammed the radar of the area which they were about to breach. This allowed the F 15 to deliver their strike package, crippling the Iraqi Anti-air defences. This meant one less thing to worry about for the rest of the operation.

Modern tanks

During the First Gulf War, Coalition forces had significantly more advanced levels of military technology - including tank technology - strategy and training than Iraqi forces. Thus, the war was an asymmetric war. In the 1990s, asymetric wars became more common when the Soviet Union fell apart and NATO countries frequently found themselves policing third world conflicts.

he United States was the leader of the Coalition, and its tank force was dominated by the M1A1 Abrams. Other important Coalition tanks during the war were Britain's Challenger 1 and France's AMX-30. There were also some American M60 Patton tanks and British Centurions.

Most of the Coalition countries used Western tanks; exceptions were Egypt and Syria, which had Soviet tanks.

On the opposing side, the majority of Iraqi tanks were T-72Ms that had been built in the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The T-72M is an export version of the USSR's T-72.

The Iraqis also had Soviet T-54/55s, T-62s and PT-76s, as well as some Chinese Type 59s and Type 69s,

Coalition tanks were vastly superior to Iraqi tanks. The Iraqis used export versions of tanks and did not have access to the latest ammunition and the latest technological upgrades.

For example, in Western tanks, night vision equipment was standard. However, most Iraqi tanks lacked night

vision equipment, although some T-55s had infrared searchlights.

In addition to having inferior tanks, the Iraqi tank force was hampered by the fact that its crews were poorly trained compared to Coalition tank crews.

Iraqi battle tactics had been influenced heavily by the experience of the long war with Iran, where artillery had played an important role in defending against human wave attacks by the Iranians. Therefore, the Iraqis were heavily dependent on artillery and had less experience with tank warfare.

The Iraqi tank crews often tried to make up for their lack of training by using their tanks for defense and fighting from dug-in positions, instead of using their tanks to fight aggressively. They would presight their weapons to specific distances and then fire. Their efforts were very uncoordinated.

Coalition troops were able to use air attacks to destroy Iraqi tanks before the ground war even started. Aircraft with thermal target equipment would discover and blow up parked vehicles while Iraqi soldiers were sleeping in them.

On the other hand, Coalition tank crews were well organized and worked efficiently along with infantry and air support.

During the ground war, Coalition forces did not attack Iraqi tanks head on. Instead the spearhead broke through the Iraqis' main defensive line, got behind it, and then moved in from the rear while other forces put pressure on the front.

Coalition tanks were able to advance so quickly that sometimes they arrived at enemy positions before the Iraqi troops even received warning of an attack.

As they broke through the front line, the unprepared Iraqi troops behind it were terrified and surrendered immediately.

The First Gulf War ended in February 1991, when the Iraqi army was defeated and Kuwait was liberated.

The Iraqis lost almost 4000 tanks.

In contrast very few Coalition tanks were lost.

It is believed that only 18 Abrams tanks had to be taken out of service during the war, most of these because of friendly fire, and that no Challenger 1s were lost to enemy fire at all. Challenger 1s are believed to have destroyed 300 Iraqi tanks.

The record for the longest distance tank against tank kill goes to a Challenger 1 in the First Gulf War, which destroyed an Iraqi tank from a distance of 3.2 miles (5.1km)